- William Shakespeare, Hamlet, quoted by Senator Lister Ames Rosewater

Act I: Shithouses, Shacks, Alcoholism, Ignorance, Idiocy and Perversion

Act I: Shithouses, Shacks, Alcoholism, Ignorance, Idiocy and Perversion

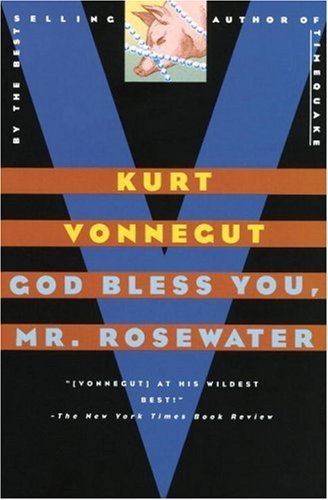

After his long time away from earth touring the solar system throughout his first four novels, Kurt Vonnegut has come back to earth for his fifth novel, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater. His postmodern odysseys have taken him to a dystopian future, the far reaches of the solar system, a Jerusalem prison cell, and an absurdist Caribbean island to witness the end of the world. In God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater Vonnegut comes back to practically his own childhood doorstep, seeing as he grew up in Indiana, the setting of the bulk of this novel about social nihilism, soul rot, and economic inequality. While Vonnegut’s wild and whirling travels through space and time are illustrative of his thoughts on the nature of society, politics, the worth of humans, and all other modern anxieties of advanced industrial society, he has yet to confront the gritty reality of post-WWII America. His escape from orbit is in many ways a desire to leave this world behind, an attempt to find a better world where the atom bomb isn’t the ultimate problem-solver and a machine can’t outrank a human in worth. He has grappled with the apocalyptic and the fear of Cold War-era American, but he hadn’t yet confronted the soul crushing meaningless of everyday life people experience while waiting for the bomb to go off. If his previous novels have largely seen Vonnegut searching out a new, more human and humane world, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater is a return to earth to confront that earthly sickness from which he is so desperately trying to escape. His previous works are largely symbolic, using a fictive Martian army to express the conformity in post-WWII American or a player piano to investigate anxieties over human superfluity. God Bless Your, Mr. Rosewater is a return to the literal – it is a realist respite for a very surrealist author.

And what, after his long odyssey, does Vonnegut find happening in post-WWII America? Nothing but “shithouses, shacks, alcoholism, ignorance, idiocy and perversion.” This is, at least, what the scene is in Rosewater, Indiana – a fictional middle-America small town overcome with industrial malaise and social nihilism. Rosewater is home to the Rosewaters, a glaring example of American royalty: a collection of politicians, industrialists, and capitalists with the ability to suck the marrow from the dry bones of the American public just long enough to hightail it to their east coast yachts and beachside properties. That is, all but Eliot Rosewater, the family black sheep, known for his perverse compassion for the common man and his disdain for worldly trappings such as wealth, power, and reputation. Eliot, after all his years in east coast boarding schools and Ivy League colleges, has decided to return to his family’s hometown to revive the Rosewater Foundation, a supposedly philanthropic organization that was really devised by family lawyers looking to avoid paying taxes on the nauseating immensity of their wealth.

Back in Indiana Eliot is estranged from his father as well as his east coast relatives, the “Rhode Island Rosewaters” who feel they are being swindled out of their fair share of the family wealth. He returns to this rotten core of industrialized America to put his family funds towards the endeavor to award humans unconditional and uncritical love – and a little money besides. Setting up shop in a disheveled apartment nearby the local fire station. Firefighters, he claims are some of the most compassionate people alive, being willing to save people with such valor. Living in a bachelor pad for the ages, a slowly decaying wreck compared to the abandoned mansion his family owns nearby, he takes calls from concerned citizens, offering advice on everything from why they shouldn’t commit suicide ("Don't kill yourself, call the Rosewater Foundation") to how to properly notarize an official document. His one ultimate maxim is: “God damn it, you’ve got to be kind.” It is here, at the rotten heart of America, that Eliot decides to confront the overwhelming madness of the world – though there are plenty who claim that Eliot is himself mad in his attempt to do this. The sniveling family lawyer Norman Mushari wants to part Eliot Rosewater’s from his millions, ostensibly for the purpose of fairly distributing it to the Rhode Island Rosewaters. All he has to do is legally prove that Rosewater is insane, making him illegible to inherit his wealth. To make his case he relies upon the “common gossip in the office” that Eliot Rosewater is a “lunatic.” Such a characterization is a playful one, Vonnegut insists, but “playfulness was impossible to explain in a court of law.” In a thoroughly bureaucratic world, the insane are made to look sane and the sane insane. Being a lunatic is a perfectly normal reaction to the horrors of industrial modernity, but the bureaucratic morasses of modern life cannot adopt a sympathetic humanist gaze to comprehend that. This is the reason the Herbert Marcuse, in his study on one-dimensional society, wrote that “the most vexing aspects of advanced industrial civilization” is the “rational character of its irrationality.” Eliot Rosewater may be thoroughly irrational – a lunatic really – but in this rationally irrational society, his attitude is, ultimately, the rational attitude. Mushari “never saw anything funny in anything, so deeply immured was he by the utterly unplayful spirit of the law.” Vonnegut humor serves to cut through the inhuman logic of mechanized society to reinvigorate human experience and understanding.

Act II: Something is Rotten in the State of Indiana

Before he settles back in Indiana Eliot decides to take a tour of the country visiting various small towns, reacquainting himself with the American proletariat, and donating money to his much beloved fire stations. While away he happens upon a town called Elsinore, which clearly strikes a Shakespearean chord in him. Penning a letter to his estranged wife, he refers to her as Ophelia and signs his name as Hamlet. Eliot, like Hamlet, is “too much in the sun.” And his relationship to his relatives, particularly his father, is “a little more than kin, and less than kind.” Eliot’s concern for the common people is disconcerting to his capitalist relatives, who which he would, in the words of the Bard, “throw to earth / this unprevailing woe.” Concern for the wretched of the earth is unnatural to them. As Claudius reprimands Hamlet:

“It shows a will most incorrect to heaven,

A heart unfortified, a mind impatient,

An understanding simple and unschooled.

For what we know must be and is as common

As any the most vulgar thing to sense,

Why should we in our peevish opposition

Take it to heart?”

Eliot Rosewater’s will is very much indeed set against heaven if heaven’s desire is for a rigid social system, which Vonnegut calls the “savage and stupid and entirely inappropriate and unnecessary and humorless American class system.” Eliot, like Hamlet, must defend himself against accusations of insanity in order to set to rights the madness of his world. Like Hamlet, he is the son of royalty, albeit American royalty. His father, besides being fabulously wealthy, is a US Senator for the state of Indiana. Thus God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater consists of Vonnegut illustrating Eliot’s compassionate insanity and everyone else’s inhumane, calculating, and all-too-rational logic.

Eliot, the prince of Indiana, fits uncomfortably in this irrationally rational society. Like Hamlet, he’s been given everything he supposedly could need in life: military honors, splendid education, millions of dollars, a beautiful wife, a sturdy body, hundreds of friends. And yet, laments his father, the Senator, “what is his reply when life says nothing but, ‘Yes, yes, yes’? ‘No, no, no.” Eliot Rosewater is a rebel, engaging in a great refusal to complacently accept the world – a world bereft of love and human compassion – as it is given to him. Eliot’s world, however, takes his refusal as madness. QuotingHamlet, Senator Rosewater laments, “What a noble mind is here o’erthrown!” Eliot is Hamlet, but an inversion version of the character. While Hamlet grieved his father’s death, Eliot’s father grieves for his son’s life. Hamlet lost a father, and Eliot’s father (believes he) lost his son. Hamlet believes he has lost everything that mattered to him while Eliot Rosewater, to the chagrin of his father, desires to lose everything that society says should matter.

What ultimately binds Hamlet to Eliot Rosewater is their lonely awareness of the rottenness of their world. For both, the world is “an unweeded garden / That grows to seed. Things rank and gross in nature / Possess it merely.” Hamlet alone knows the depths to which his Denmark has plunged and the utter corruption that eats away at its and his heart. Likewise, Vonnegut portrays Eliot as being one of the few humans that not only experiences the rottenness of the world but seems to know why it is so rotten: capitalism. It is the class system that is most foul, strange, and unnatural while “the funeral baked meats” of the dispossessed “did coldly furnish forth the marriage tables,” of the bourgeoisie. In Hamlet, the root of this sickness is a corrupt monarch, guilty of fratricide, regicide, and light incest – as well as the hyper-militarization of society and vague troubles in international politics. In God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater the root of the sickness is money. Money, Vonnegut writes in the very first lines of the novel, is “a leading character in this tale.” The lengths that people will go to acquire bits of “worthless paper” is immense – and the result of this lust for wealth has induced a fatal sickness in society.

While it may be true that, in a strictly psychological sense, Eliot Rosewater may be mad, his mind is still the sturdiest indicator of humanity and humaneness in this condition of world-historical sickness. One character exclaims that Eliot is, “the only American who has so far noticed the Second World War” – mainly because it largely drove him insane. Hamlet too was one of the few who knew the degree to which is world was corrupted. This is clearly how Vonnegut sees himself – the only American that has noticed war, along with all the other abominations of human ego and industrialism. To be so affected by things like war may lead to clinic insanity, but socially and historically, it is the sanest reaction of all.

Vonnegut paints an unblemished picture of Eliot Rosewater’s madness. He admits that Eliot is a “drunkard, a Utopian dreamer, a tinhorn saint, an aimless fool.” Eliot and his wife are described as “two such sick and loving people” that are constantly in psychoanalysis, undergoing electroshock and chemotherapy, and are thoroughly unable to lead anything resembling an ordinary and stable life. But accusation of insanity are not meant as censures – it is in fact the thoroughly sane for whom Vonnegut reserves his disdain. Who could blame Hamlet for his insanity? Perhaps the actions undertaken during his insanity are reprehensible, but the insanity itself is a perfectly reasonable reaction to an insane world. After all, it isn’t really Eliot or Hamlet that are insane, but the world itself. Their only fault lies in their expecting the world to be a decent and honorable place, a naivety that Vonnegut prizes above all else. Eliot’s goal is – against all odds – to “love everybody, no matter what they are, no matter what they do.” This is what truly earns him the label of insanity. Even the wretched figures he cares for in his Indianan hometown recognize this: “people are going to think you’re crazy for paying so much attention to people like us.” Vonnegut doesn’t dispute such an accusation, for it truly is crazy to have so much concern about the dispossessed and downtrodden – but it is such craziness that we so desperately need more of. This is what largely separates Eliot’s madness from Hamlet’s. Instead of the solipsistic moaning of the pathetic Hamlet, Eliot, as one character lauds him, “gave up everything a man is supposed to want, just to help the little people.” For this, she praises him: “God bless you, Mr. Rosewater.” From this it must be concluded: God bless insanity.

The world of God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater is a surprisingly realistic take on modern America. Gone are the aliens and time travel that Vonnegut so comfortably works into his social and political analyses. We are left with the gritty and disappointing soul-rot of Cold War-era America. This is a world where, as Vonnegut writes, lives are “nearly all paltry, lacking in subtlety, wisdom, wit or invention,” and thoroughly “pointless and unhappy.” The whole of advanced industrial America is rotten to the core with a fatal sickness of the spirit, a bleak social nihilism from which we may never recover. People are constantly being “rejected as being mentally, morally, and physically undesirable.” That anyone could make a fortune on stocks and bonds – “small experiments with worthless paper” – while laborers starve on the streets indicates that something is very rotten indeed.

Vonnegut’s class analysis shines through in this tale of gruesome realism: “the least a government could do, it seems to me, is to divide things up fairly among the babies. Life is hard enough, without people having to worry themselves sick about money, too. There’s plenty for everybody in this country, if we’ll only share more.” Vonnegut spoke openly about his admiration for the American socialist leader Eugene V. Debs. His words resonate strongly with Debs, who once stated his opposition to capitalism as such: “I am opposing a social order in which it is possible for one man who does absolutely nothing that is useful to amass a fortune of hundreds of millions of dollars, while millions of men and women who work all the days of their lives secure barely enough for a wretched existence.”

The real sickness at hand is the mere fault of being human in an era in which humans have become superfluous – insufficient at completing the mechanized and mindless tasks of industrial society. “Can I help being human?” Eliot’s wife asks him. “Not that I know of,” he replies. People have been reduced to unthinking and unfeeling machines – “they have lost all semblance of human beings except that they stand on two feet and talk – like parrots.” Money, one character perversely exclaims, has become the “most important single determinant of what you think of yourself and what others thing of you.” The time when men worked with their hands and backs is all over, “they are not needed,” laments Vonnegut. Obedience is crucial – obedience to religion, to rigid social norms, to the cult of the self-made man in a world in which to be human is a debased thing. Even something so basically human as sexuality can only be experienced through the most degrading smut. One character is shown to be admiring a photograph of “two fat, simpering, naked whores, one of whom was attempting to have impossible sexual congress with a dignified, decent, unsmiling Shetland pony” – a favorite example of Vonnegut’s that appears in other novels. Surely there is something sick about this – but it really the world that is sick at heart, not the few deranged individuals looking for escape. It is a world in which, as Marx described, “man (the worker) only feels himself freely active in his animal functions… and in his human functions he no longer feels himself to be anything but an animal. What is animal becomes human and what is human becomes animal.” Vonnegut, via Eliot Rosewater, is attempting to overcome the vicious separation of man from animal that the dehumanizing system of capitalism necessitates.

Act III: The Sickness Unto Death

Kierkegaard, in his text The Sickness Unto Death, describes humanity as balancing between polarities such as the "finite and infinite" and the "possible and the necessary." The tension between these opposing forms a dialectic against which the self can be defined. Similarly, Vonnegut exposes the dialectical progression of history – including its crushing contradictions and especially its dispossessed. For Kierkegaard the sickness unto death is the inability of the self to reconcile with the dialectic of finite and infinite and the despair that it elicits. Vonnegut sees the social sickness unto death as the inability of the historical subject – the historical self – to grapple with the dialectic of history and align that self towards existential, rather than deterministic and utterly grim ends. When the self is unable to pry itself from despair over the dialectic, when Sisyphus is not happy, determinism is overwhelming and nihilism (social, metaphysical, and political) sets in.

Kierkegaard posits faith as the opposite of despair. His, of course, is a deeply Christian faith, which he describes as "In relating itself to itself, and in willing to be itself, the self rests transparently in the power that established it." That power is, in Kierkegaard’s estimation, God. In a secular version of this, which suits Vonnegut, a secular absurdist himself, this could be restated in the following way: "In relating itself to itself, and in willing to be itself, the self rests transparently in the power that established it, which is itself the self." This is the self overcoming – or breaking free from – history and all the perceived determining forces that act on a self, such as social convention or dogmatic ideology.

Eliot is himself not sick, but he lives in the age of sickness, a time when history has been thoroughly overcome with the nausea of control and inevitability. When Eliot enters psychoanalysis he can’t speak of his own neuroses, but instead, according to his analyst, talks exclusively about American history. When asked to explain his dreams for analysis, he tells his analyst “Samuel Gompers, Mark Twain, and Alexander Hamilton.” He insists on reciting “well-known facts from history, almost all of them related to the oppression of oddballs or the poor.” The doctor, fed up with Rosewater, insists that there is no cure. Rosewater counters, “It’s a cure he doesn’t understand, so he recuses to admit it’s a cure.” The cure is for a historical sickness – it is a cure for the sickness that is history itself – which is why his analyst is helpless.

If psychoanalysis won’t help, then what is the way to overcome this world-historical sickness? It must consist in overcoming world history itself. History itself is rotten through. Vonnegut describes a relative of Eliot – Fred Rosewater – who despairs in his seeming insignificance in the state of world history. Fred, to his delight, comes across a manuscript detailing his family history. Enthralled by the adventurous exploits of his ancestors he is distraught to find that, besides the first few pages, this history of his family is literally rotten, eaten away by worms. Once again, Fred finds himself without a sense of purpose, unable to be comforted by the idea of continuing a genealogy of which he could be proud. The literal rottenness of history evokes the metaphoric rottenness that Fred is blind to. Fred wants to willingly subject himself to a determinism where he can play a part in something someone else has written. He would rather act than live, rather mimic than create, and rather accept a history as an inexorable progression than write his own history and leave the rotten history to the worms where it belongs.

Fred should have taken his cue from the original Rosewater, one of the only ancestors he could read about before finding that the manuscript was rotten. This first Rosewater, originally John Graham, moves to an island off the coast of England, and becomes a poet and a farmer “far from the centers of wealth and power.” Why he changed his name to Rosewater is not entirely clear, but Vonnegut speculates that perhaps he was “sickened by all the bloody things he saw” in the world. By this Vonnegut means John Graham wished to escape the dreadful dialectic of history, the succession of bloodied kings and violence, and make it on his own by living a purposeful and aesthetic life. This Thoreauvian aspiration drives much of Vonnegut’s post-historical imagination and speaks to the need to create an alternative history that can shed the atrocities of the past and open forth to a liberated future.

While Fred Rosewater could not willingly relinquish the history he so wished to rely upon, Eliot Rosewater had no such qualms. Eliot recognizes that absence of history is an opportunity, a chance, like his great forefather John Graham, to restart his own history and to be free from the bloody determinism of history by creating the self and its new legacy. Disregarding the past is an emancipatory strategy and a decision to not be beholden to expectations of inevitable progression. Eliot finds himself in such an amnesiac position at the end of the novel. Due to his fragile psychological state he forgets almost his whole life’s history. His insanity getting the better of him, he hallucinates vividly of the destruction of the world before forgetting years of his life. He is not worse for it though. When he awakes from his soporific forgetting he may have forgotten the details of people’s lives – even his own – but he has retained the humanist acuity necessary to lead a good life and treat people decently, something seemingly bred out of most humans. He has forgotten history but remember humanity.

At the end of the novel he finds himself in the company of Kilgore Trout, a science fiction novelist that appears in a number of Vonnegut’s works to serve as something of an alter ego for Vonnegut. Trout explains that Eliot has led a grand social experiment trying to find out how it is possible to love people who have no use. After all, “if we can’t find reasons and methods for treasuring human beings because they are human beings, then we might as well, as so often been suggested, rub them out.” Eliot thus finds himself in the position of needed a new history – a humanist tradition which posits the human at the most important figure, rather than abstract constructs such as progress or profit. Eliot comes to find that due to his great wealth and seeming generosity, fifty-six women in his hometown had made paternity suits on him in a fairly shameless attempt to extract some money out of him. Though there was absolutely no validity to this claim – after all, Eliot is as sexless as a mannequin – he gladly accepts paternity for these poor souls, and writes them all a check accordingly. Thus not only does Eliot redistribute the wealth for which he rightfully feels ashamed to have inherited, he also recreates a genealogy based on this false paternity. Though the biological paternity is not valid, he has reformulated a new genealogy by sacrificing his own wealth and power and willing it to his new “descendants,” which will surely be as numerous as the stars in the sky and as the sand on the seashore. He rejects the covenant of capital and history and creates a new covenant in which he is the patriarch of a new, humanist tradition. Eliot desires to begin the world over again, but this time he will found a new genealogy with a history of redemption, rather than exploitation and dehumanization.

Act IV: Location: A firehouse. Elisinore, California. Enter Hamlet, William Shakespeare, Terry Eagleton, Eliot Rosewater, Kurt Vonnegut.

The connections between Hamlet and God Bless You Mr. Rosewater are more profound than Eliot Rosewater visiting the an American town of Elsinore (the team was so bad they were called The Melancholy Danes) or that he wrote a letter to his fiancé as one from Hamlet to Ophelia. It goes beyond Vonnegut mentioning that one of Eliot’s favorite Kilgore Trout novels is titled 2BRO2B, a supposed take on “the famous question posed by Hamlet.” The connection is that Eliot Rosewater sees himself as a Hamlet in his own story. He, along with Vonnegut, is sick to death, not because of any internal illness, but because of the sickness of the world around him. Instead of pouring his emotional energies into the loss of his father figure, as Hamlet did, Eliot pours his love out equally to all humans. This futile attempt to confront the sickness of the world is what ultimately draws Hamlet, Eliot Rosewater, Shakespeare, and Vonnegut together.

Hamlet, according to literary theorist Terry Eagleton, is an exceptional literary figure because he is trapped between two epochs – eternally torn between past and future and wracked by its resultant historical and personal tensions. Though the plot points towards drama and tragedy, of even greater interest is how Hamlet sees himself in relation to the madness of his sickly world. He has, Eagleton argues, to possibilities for conceiving of himself. That is, he is a character trapped between two competing subjectivities, both informed by their historical circumstance. On the one had Hamlet experiences his subjectivity through the historical lens of monarchy and feudalism, with its concomitant traditionalism, patriarchy, rigid religious dogmas, and fixed state of being. On the other hand Hamlet senses the approaching wave of bourgeois individualism – what Eagleton calls the “private enterprise of the self” – which was only just beginning during Shakespeare’s time. His subjectivity is thus trapped, a condition only exaggerated by the dramatic plot unfolding around him in the royal court of Denmark. Hamlet is a transitional figure, marking historical change by being “strung out between a traditional social order” and “a future epoch of achieved bourgeois individualism which will surpass it.” Because of this, Hamlet often feels like a very modernist character, balancing tradition and the highly anticipated future. Furthermore, because Hamlet leaned towards that epoch of bourgeois individualism, a period that may itself be drawing to a close, he speaks to our times. We too are torn between paradigms of traditionalism and the uncharted waters of the future. While bourgeois subjectivity was novel for Hamlet – and highly progressive – it has become regressive in our times, and thus we find ourselves reenacting Hamlet’s struggle, seeking out new forms of subjectivity to match our aspirations and to break free from the stultifying past. We, as Eagleton writes, “gropingly feel our way” towards new subjectivities just as Hamlet did, although we do it to break free from that bourgeois individualism which represented social progressiveness in his time.

Eagleton proposes that the conflicts of body and ideology in Shakespeare’s writing serve as allegories for class struggle and reflected anxieties about the rapidly changing political and economic structures of his times. Shakespeare bared “the burden of a class society in crisis.” Because of that, Eagleton sees a deep connection between Shakespeare’s period and our own, particularly as represented ideologically by Hamlet’s tensions of subjectivity. However, while Shakespeare’s period was not ripe for a truly revolutionary class struggle our time may be, in that “the exploited and dispossessed have now become an historical force to be reckoned with.” Eagleton’s writing on Shakespeare (and Hamlet in particular) reveals his deeply modernist reading of the Swan of Avon as well as his desire to reinvigorate Shakespeare’s ideologically and politically tense characters to reflect the concerns of today. Hamlet is a progressive character – for his time – and it is necessary to reformulate such progressiveness for the end of bourgeois hegemony and to spell out the possibility of a liberate humanity. Eliot Rosewater, the protagonist of God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, is such a character. Terry Eagleton describes Hamlet as a loiterer, who is “unable and unwilling to take up determinate position within” society and “spends most of his time eluding whatever social and sexual positions society offers him.” This loitering behavior applies to Eliot Rosewater as well, who becomes estranged from his wife, childish and desultory in his naivety, and thoroughly genderless and sexless.

Eliot Rosewater too straddles historical epochs: that of bourgeois individualism and self-interest and an as yet not existing form of subjectivity. He, like Hamlet, is “never identical with himself,” as Eagleton describes Hamlet. Eliot recognizes that individualism – the enterprise of the self – is far too solipsistic in times in which sociopolitical nihilism has become the norm. In an era in which the press of a button can set off a nuclear holocaust it is far too risky to raise oneself above all others in import and prestige. Paradoxically though, this rejection of solipsism necessitates a return to the self and involves self-work. Part of rejecting the self-absorption of bourgeois individualism is the ability to recognize the responsibility of the self in society. “This psychological regression,” Eagleton claims for Hamlet, “is also, paradoxically, a kind of social progressiveness.” Eliot too rejects the traditional patriarchal trappings and renounces his claim to the throne in order to serve what he perceives as a greater purpose. Eliot Rosewater too renounces his claims by donating money to his estranged relative and giving money to all those who have made paternity claims on him. The loss of a mother figures into both Eliot and Hamlet’s imagination. The self must be reconfigured as a social self, one that constantly enters into social relationships and affects other selves in a deeply phenomenological sense. This return to the self is, contradictorily, a rejection of individualism. The self, in short, is a social self, something Hamlet failed to recognize – much to the detriment of those around him who faced the consequence of his destructive conception of the individual self.

Act V: The Bard of Indiana

If Eliot Rosewater is the modern Hamlet, then Kurt Vonnegut is the modern Shakespeare. This analogy is surely hyperbolic, but it has an undeniable ring of truth. Both Shakespeare and Vonnegut convey complex philosophical and political concepts in fairly simple and popular terms (contrary to his rigidly highbrow status now, Shakespeare’s plays were very much popular among working class populations during his time, although his English sounds oddly formal today). Both writers were concerned with the role of art in society and struggled with the desire to change the world versus the inability to truly impact the course of historical events. Hamlet feels the paralyzing anxiety of inaction as he contemplates whether human existence is worthwhile at all. Eliot Rosewater similarly experiences something Vonnegut calls “Samaritrophia,”that is, a “hysterical indifference to the troubles of those less fortunate than oneself.” Eliot’s wife in particular experiences an acute form of this psychological disorder, which arises not because she truly doesn’t care for anyone, but because she is driven to madness by her paradoxical desire to make the world better and the inability to make any positive changes in this sickly world. In response, she completely gave up trying to help people at all and showed a sociopathic indifference to humanity. To cure her, her doctor engages in some combination of “chemotherapy and eclectic shocks” to change her personality. Her new medically prescribed personality was one of superficiality. The goal was to make her, like most people, care only slightly about humanity and not be perturbed by the ineffectiveness of most attempts to change the world for the better. In this technocratic world, it is up to the doctor to determine how much guilt and pity she ought to feel. The doctor in this case is slightly horrified, for he had “calmed a deep woman by making her shallow.” He exclaims: “Some doctor! Some cure!”

The paralyzing of the self strikes at the heart of both Hamlet and God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater. The melancholic indifference of Hamlet would fit in well in the slums of Rosewater, Indiana. Terry Eagleton describes Hamlet’s melancholia as that which “drains the world of value and dissolves it into nauseating nothingness.” This is not far from Vonnegut’s Samaritrophia – though the later has important social and political connotations that Hamlet’s solipsism does not. Nevertheless, Hamlet, as Eagleton conceives him, “falls apart in the space between himself and his actions.” This derives from an incommensurability between the self and the idea of the self as well as between the world and the idea of the world. Theory and practice are misaligned, shattering a complete understanding of self. Hamlet and Eliot Rosewater alike lament, “The time is out of joint. Oh, cursed spite / That ever I was born to set it right.”

Shakespeare often meditates on the role of artists in society and puts forth competing ideas on how the aesthetic can mix with the political, the social, and the historical. Vonnegut too is preoccupied with this issue, and frequently illustrates his vision of an aestheticized humanity. In God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater he ironically pronounces some casual advice: “You can safely ignore the arts and sciences. They never helped anybody.” At the same time, his praise of the arts is strewn across this novel. One character admonishes an insurance salesman: “Why be an insurance bastard? Do something beautiful.”

Perhaps the greatest defense of the arts comes in Eliot Rosewater’s madman rant at a science fiction conference. Engaging in some blatant meta-fiction, Vonnegut, via Eliot gives an impromptu speech praising science fiction writers, saying he only reads that genre because they are “the only ones who’ll talk about the really terrific changes going on.” They are the only ones with “guts enough to really care about the future, who really notice what machines do to us, what wars do to us, what cities do to us.” Science fiction writers are the diagnosticians of modern life. They are “the only ones zany enough to agonize over” the mysteries of the present and the sickness of society. This is meta-fiction, because Vonnegut is himself a science fiction writer, although God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater isn’t itself science fiction. Eliot later admits that “science-fiction writers couldn’t write for sour apples, but he declared that didn’t matter. He said they were poets just the same.” For Eliot, just as with Vonnegut, what matters is that they are “more sensitive to important changes than anybody who was writing well.”

Though this is not a work of science fiction itself, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater reveals itself to be a tender paean to the science fiction sensibility. It is a call to imagine, among other things, news ways to circulate money. More broadly, Vonnegut wants to reimagine history and historical possibility. This is why, when in analysis, Eliot Rosewater only speaks of American history. We live in a sick and troubled world the cause of which is a faulty history. The mass neuroses and psychoses in the world are not, at root, psychological. There is a political an historical (and perhaps even metaphysical) sickness in society Vonnegut seeks to treat with his potent imagination. Science fiction writers, he argues, are best suited for this treatment. Their imagination is a curative one. This is a tongue-in-cheek naive belief, but this novel is nothing if not in praise of the naive and innocent foolhardy dreamers of a world with more sense and less pain. There are more things on heaven and earth, after all, than are dreamt of in unimaginative philosophies. Hamlet opined that he "could be bounded in a nut shell and count / myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I / have bad dreams." Vonnegut's appeal is for new dreams for an emancipated humanity.

Though this is not a work of science fiction itself, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater reveals itself to be a tender paean to the science fiction sensibility. It is a call to imagine, among other things, news ways to circulate money. More broadly, Vonnegut wants to reimagine history and historical possibility. This is why, when in analysis, Eliot Rosewater only speaks of American history. We live in a sick and troubled world the cause of which is a faulty history. The mass neuroses and psychoses in the world are not, at root, psychological. There is a political an historical (and perhaps even metaphysical) sickness in society Vonnegut seeks to treat with his potent imagination. Science fiction writers, he argues, are best suited for this treatment. Their imagination is a curative one. This is a tongue-in-cheek naive belief, but this novel is nothing if not in praise of the naive and innocent foolhardy dreamers of a world with more sense and less pain. There are more things on heaven and earth, after all, than are dreamt of in unimaginative philosophies. Hamlet opined that he "could be bounded in a nut shell and count / myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I / have bad dreams." Vonnegut's appeal is for new dreams for an emancipated humanity.

Something Eliot greatly admires about Kilgore Trout, the author of pulp science fiction novels, his tendency to “describe a perfectly hideous society, not unlike his own, and then, toward the end, to suggest ways in which it could be improved.” He is a diagnostician for the sickness in the world, not unlike Vonnegut himself and, in many ways, Shakespeare. Vonnegut and Shakespeare alike create characters struggling with the tension of the self and attempting to survive the dialectic of history. Shakespeare straddled pre-modern and modern epochs while Vonnegut straddled the modern and post-modern. Both writers diagnosed the sicknesses of their times and offered up their aesthetic cure for willing readers. While Shakespeare wrote centuries ago, we are, as Terry Eagleton once wrote, still catching up to him – the same is must be said for Vonnegut, as we imagine new histories, new politics, and new ways of being human.

Exuent